Declining Aid in a Time of Rising Needs: Syria’s Humanitarian Crisis

- Issue 7

On 17 March 2025, the European Union hosted the Ninth Brussels Conference on Supporting the Future of Syria and the Region—the first to take place since the fall of the Assad regime. In total, EUR 5.8 billion was pledged in grants and loans for 2025 and beyond for Syria and the region. Yet behind this seemingly large figure lies a more sobering truth: real humanitarian support to Syria continues to decline, especially when adjusted for inflation.

The response is mostly funded through grants—which do not require repayment—and loans, which should be repaid and are often extended to neighbouring countries rather than Syria-based institutions. Of the EUR 5.8 billion pledged, EUR 2.93 billion was earmarked in grants for 2025, along with EUR 1.29 billion for 2026 and beyond, and EUR 1.6 billion in loan pledges for 2025 and beyond. It’s important to note that pledges for future years (e.g., 2026) are provisional and might change the following year. For the purposes of this article, we focus exclusively on pledges made for the same year in which the conference took place, in order to ensure consistent year-on-year comparisons.

Compared to 2024, when EUR 3.85 billion in grants was pledged, the EUR 2.93 billion pledged for 2025 represents a 24% nominal decrease—and an even steeper 36% drop from 2023, making it the lowest single-year grant pledge since the donor conferences began in 2016.

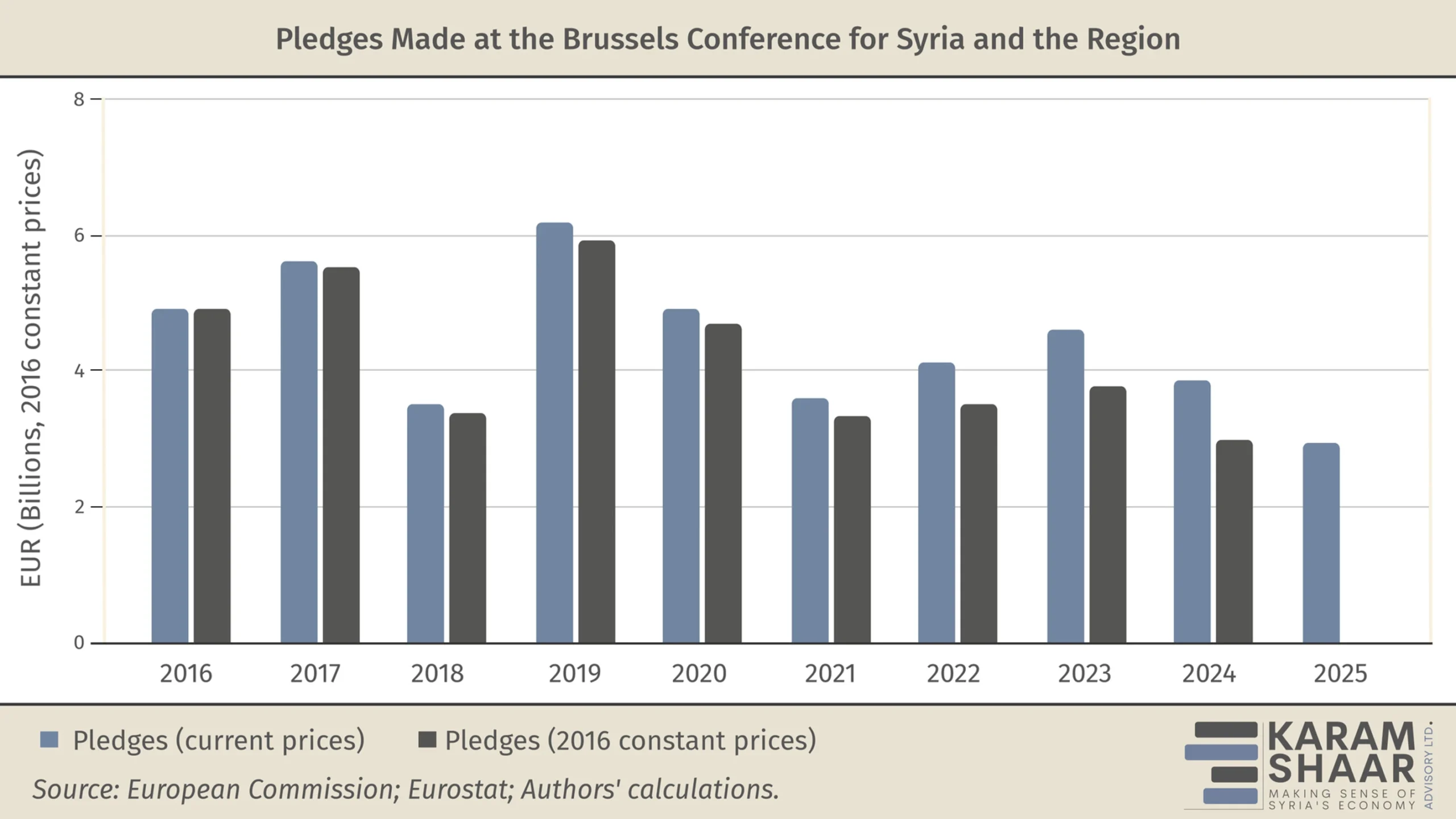

As commentators and politicians get fixated on headline figures, the erosion of money’s purchasing power often escapes notice. Adjusted for inflation, the decline in aid is even more evident. Due to the absence of reliable consumer price data covering the whole of Syria, we rely instead on a proxy measure for inflation in donor states, covering the largest collection of donors: the EU and its member states. Using the EU’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices, pledges have dropped by 39% between 2016 and 2024 in constant 2016 euros. For 2025, the outlook is equally bleak: current pledges are already the smallest ever recorded in nominal terms, and inflation-adjusted values are expected to be even lower, with inflation continuing to rise.

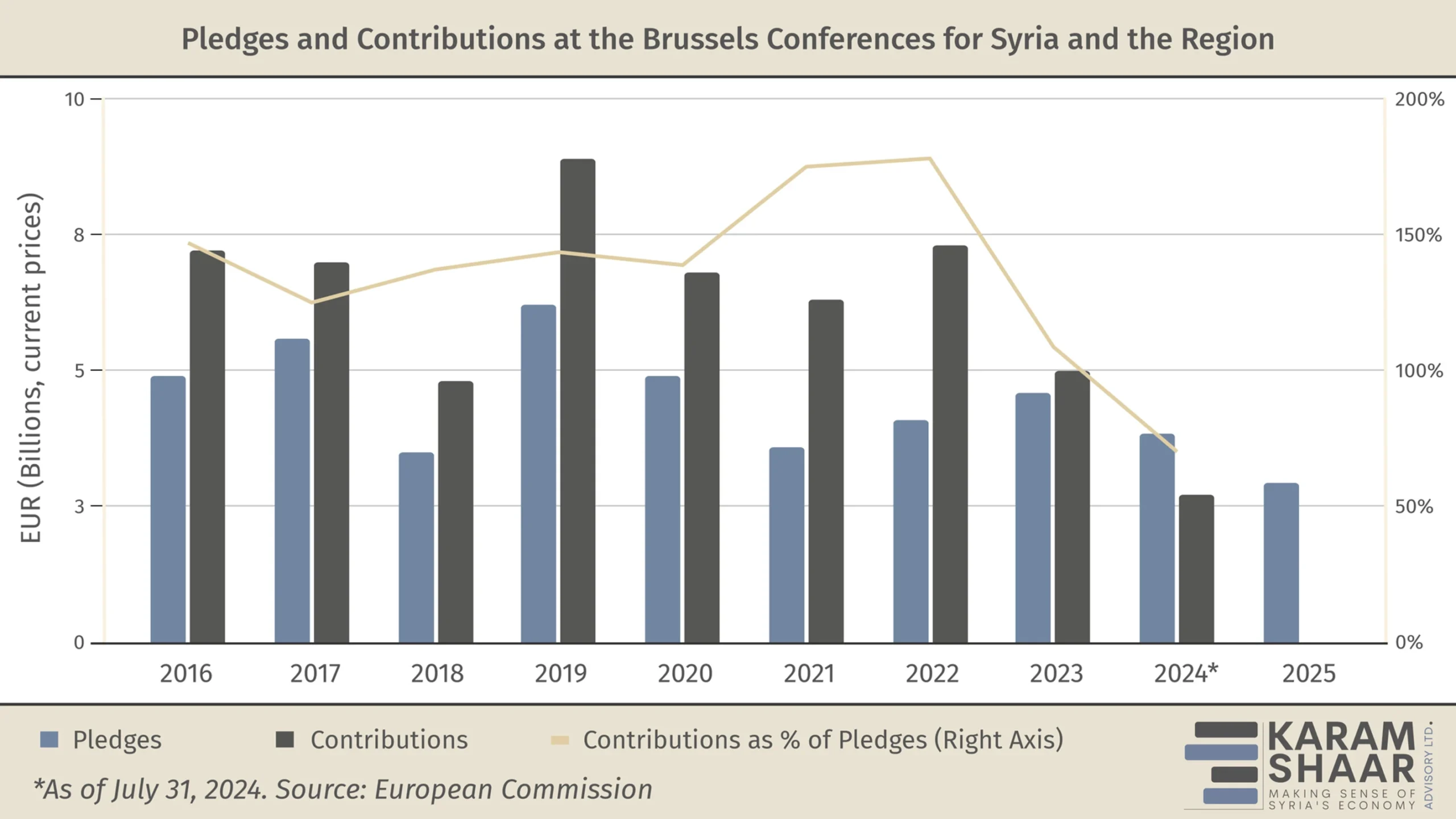

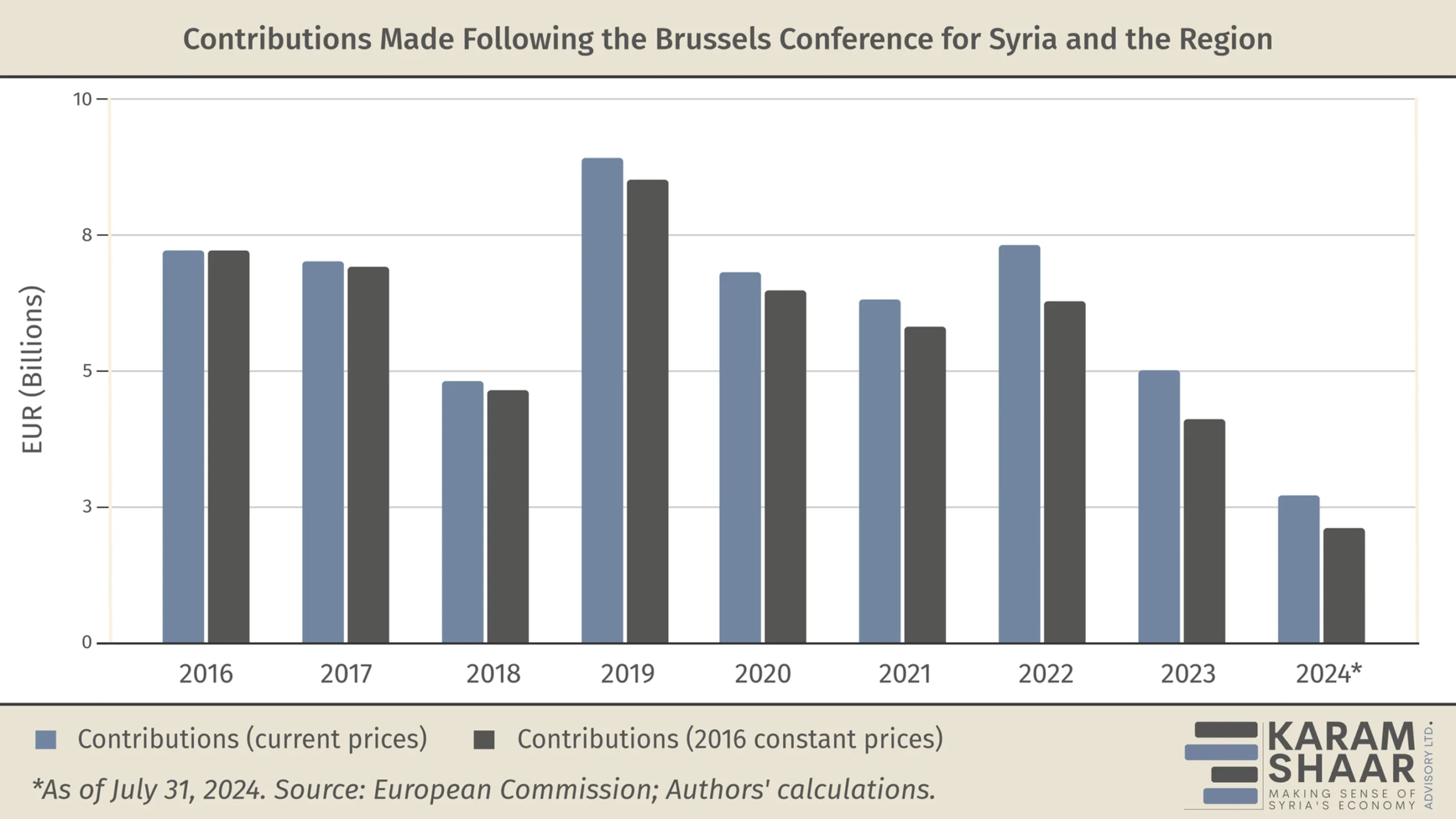

As with pledges, not only are contributions—the actual funds committed, contracted, or disbursed–lower in nominal terms, they also buy significantly less than they once did. For example, 2022 contributions of EUR 7.3 billion were the second-highest in nominal terms, but only the fifth highest in constant 2016 euros, amounting to EUR 6.3 billion. Furthermore, while contributions often exceeded pledges in the past (125%–178% between 2016 and 2022), recent years show a sharp decline with the ratio falling to 109% in 2023.

Preliminary figures for 2024 suggest a continuing decline. With EUR 2.7 billion contributed by July, and assuming monthly contributions carrying until the end of the year at the same pace, total contributions would reach around EUR 4.62 billion in current prices. Yet in constant euros, this would amount to only EUR 3.2 billion—a 21% year-on-year decline, and the lowest in real terms since the inception of the Brussels Conferences.

UN Programs Falter

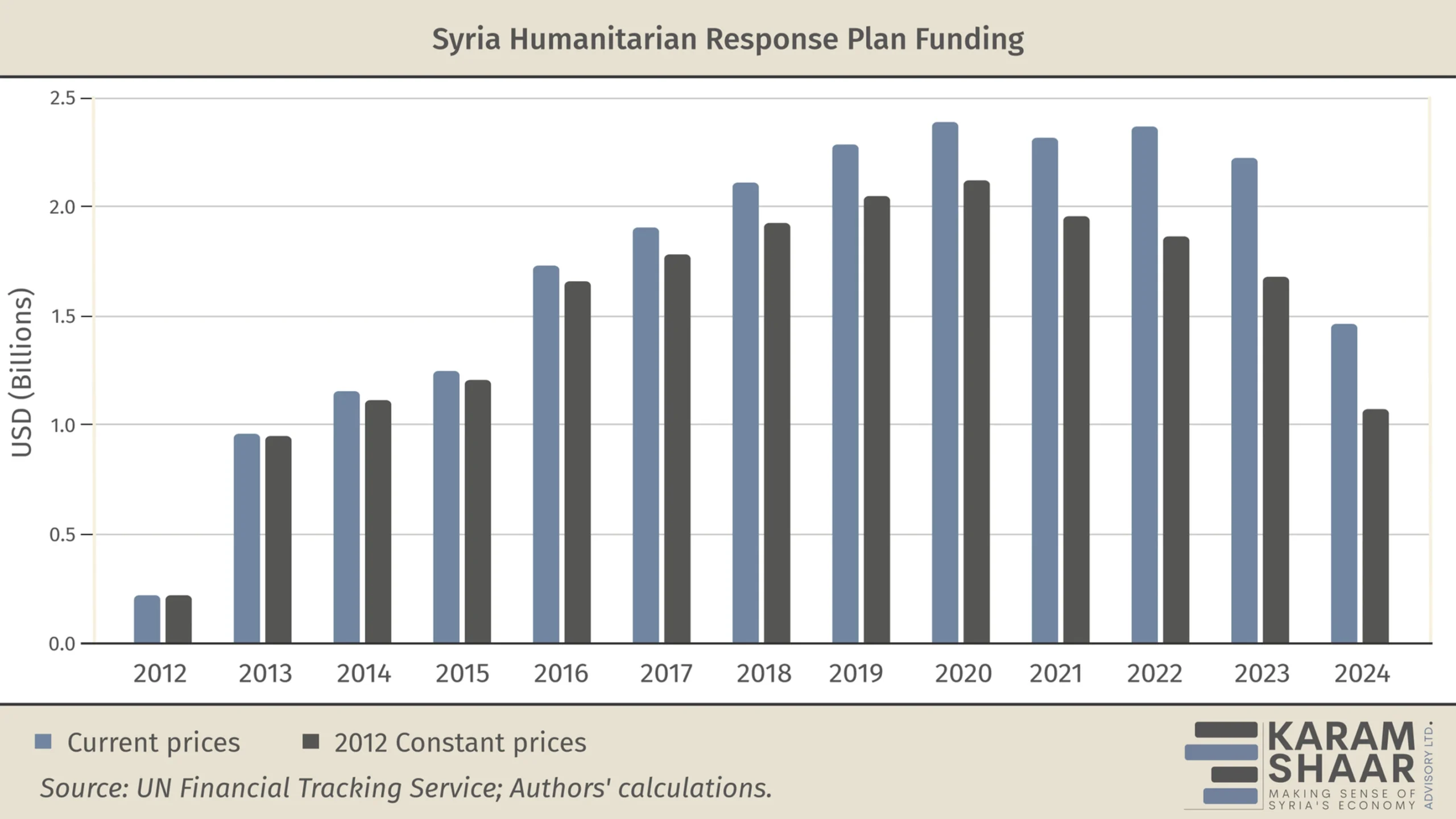

Another way to assess the drop in aid to Syria is to examine the figures from UN-coordinated humanitarian aid programs, which constitute the largest bulk of humanitarian spending.

Brussels Conference pledges include both humanitarian and non-humanitarian funding, making them broader in scope than the UN-coordinated Syrian Humanitarian Response Plan (SHRP) tracked by the UN Financial Tracking Service (FTS). The FTS captures only allocations made under UN-coordinated aid programs.

This difference partly explains why the Brussels Conference and FTS figures do not generally match. For instance, in 2023, Germany’s contribution to the SHRP was reported as USD 315 million via FTS, compared to approximately USD 395 million recorded in the Brussels tracking system. Similarly, France’s contribution was USD 61 million under FTS, versus approximately USD 85 million (EUR 79 million) in the broader Brussels figures.

Figures tracked by FTS paint a much bleaker picture of the decline in aid than the numbers reported through the Brussels Conference contributions, suggesting a donor shift away from the UN as a funding vehicle.

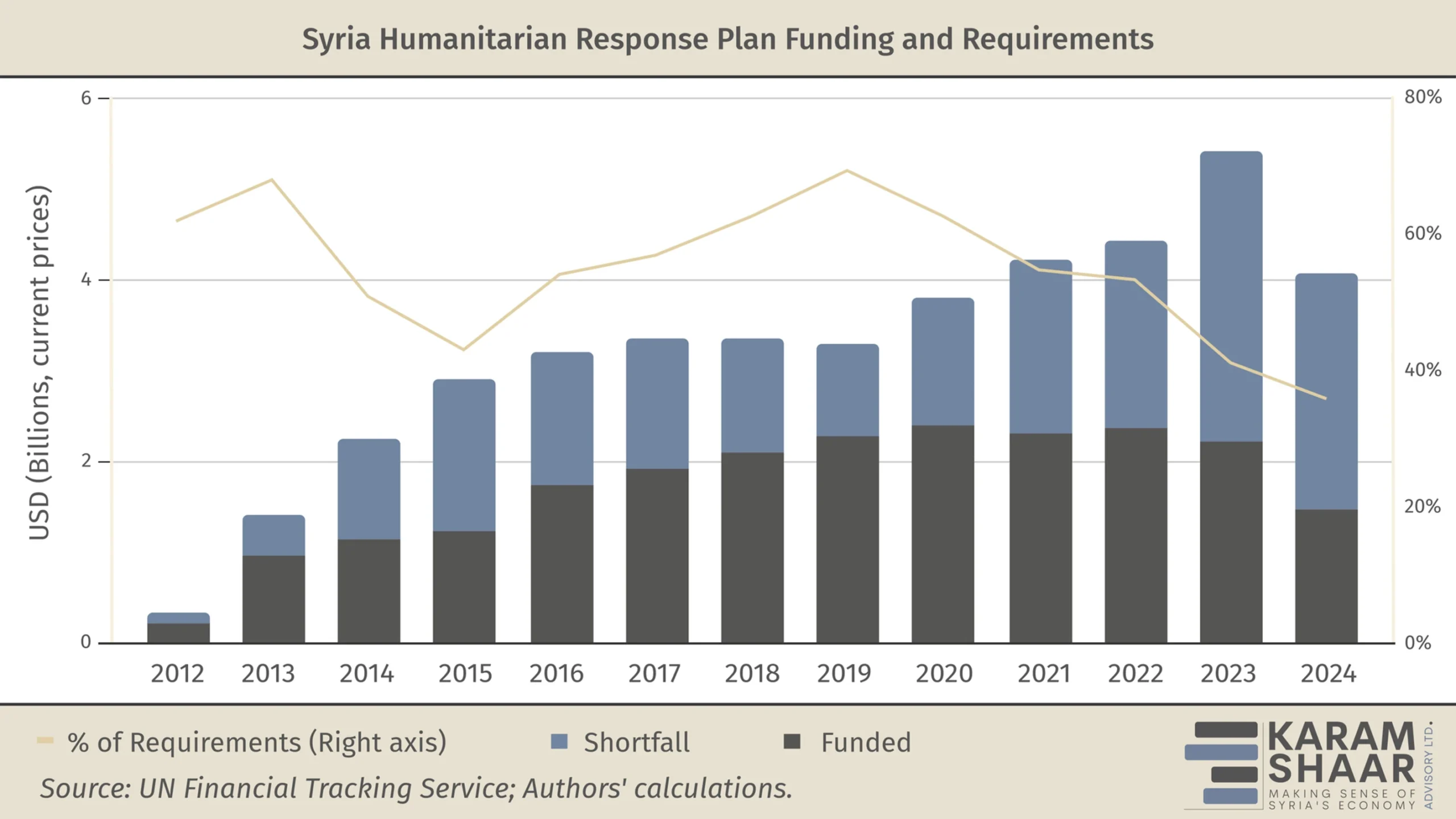

In 2020, SHRP funding peaked at USD 2.4 billion (current), equivalent to USD 2.1 billion in 2012 dollars. But by 2024, funding dropped to just USD 1.5 billion, which equals a mere USD 1.1 billion in constant dollars—a nearly 50% real decline in just four years. In fact, 2024 marks one of the third lowest levels of real humanitarian funding under the UN-sponsored programs since the crisis response began in 2012.

It is possible that the full picture for 2024 has yet to emerge, as some 2024 data on funding may still be reported into mid-2025. However, the figures currently available align with public statements by UN officials citing that only 35% of requirements have been fulfilled by contributions.

This decline is particularly alarming given that funding requirements steadily increased every year between 2012 and 2023, peaking at USD 5.4 billion in 2023 before seeing a drop in 2024. Yet, despite these rising needs, the funding fulfillment rate hit a record low in 2024, with only 36% of requirements met.

Looking Ahead: Political Momentum, Humanitarian Gaps

In spite of the consecutive decreases in aid that Syria has witnessed over the past years, humanitarian needs have never been higher—a dynamic that is increasingly circular, as underfunding itself can contribute to the further deterioration of living conditions. The outlook in early 2025 remains deeply concerning.

Despite the regime change, the number of people in need continues to grow. UN agencies estimate that over 16.7 million Syrians require assistance—the highest figure since the conflict began. This includes 7.4 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and more than one million recent returnees, many of whom are arriving to destroyed homes and areas plagued by infrastructure collapse.

In response, the UN launched a USD 2 billion appeal for the first half of 2025 to reach just 8 million of the most vulnerable. Yet by late March, only 8% of that target had been funded. The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has warned that continued underfunding will result in even greater costs—for both Syrians and regional stability.

Challenges to humanitarian funding, such as the US administration’s suspension of aid, risk having a detrimental impact during this critical period. The severe shortfall is already creating major operational constraints for humanitarian organizations. In a briefing to the UN Security Council on 25 March 2025, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator Tom Fletcher noted that almost half of US-funded organizations have received full or partial stop-work orders, and that humanitarian staffing has been cut by 40%. This reduction in capacity is severely hampering the delivery of life-saving assistance.

While the lack of funding lies at the heart of the issue, another continued challenge to humanitarian operations in Syria stems from the continued enforcement of UN and US sanctions. While not directly targeting humanitarian actors, these measures have produced far-reaching indirect consequences that significantly hinder relief work. As noted in previous issues of Syria in Figures (February and March 2025), lingering financial restrictions have disrupted agencies’ ability to process cross-border payments. Sanctions-linked obstacles have delayed procurement, increased operational costs, and often forced aid agencies to rely on informal financial networks—raising serious transparency and accountability concerns. Easing sanctions would undoubtedly streamline humanitarian operations and enable more direct, timely, and accountable delivery of aid—in sum, managing to do more with less as humanitarian funding continues to decline.

As Charles Lister noted in our March issue: “While Assad’s departure has unlocked the door to recovery, the door itself can only be opened by sanctions relief—principally from the US government.” This statement holds true not only for broader economic recovery, but also for ensuring the continuity and effectiveness of humanitarian aid.